Chapter II: The theoretical basis

The Conflict: 97–98

these schemes…increase the speed of traffic and… introduce traffic into streets where it is quite un-suitable

The Conflict

97We concluded in the first chapter that to deal with traffic in towns involves a question of design, that is to say of re-designing the physical arrangement of the streets and buildings in order to cope better with the use of vehicles. We are now in a position to define this problem of design precisely: it is to contrive the efficient distribution, or accessibility, of large numbers of vehicles to large numbers of buildings, and to do it in such a way that a satisfactory standard of environment is achieved. How is this to be done in existing towns and cities with their established complex pattern of buildings and their medieval networks of narrow streets? Quite obviously it is a most difficult task. An inherent difficulty is that the two components of the problem–accessibility and environment–tend to be in conflict. A good environment in the special sense we use the term could be secured overnight by reducing the traffic in every street to appropriate levels. In some places this might not cause any real hardship to vehicle users (e.g. the establishment of a ‘play street’) but as an overall policy for a town it would seriously interfere with the functioning of the place. On the other hand the accessibility problem would certainly not be solved by sacrificing environment—it has practically been sacrificed already yet accessibility still presents difficulties.

98

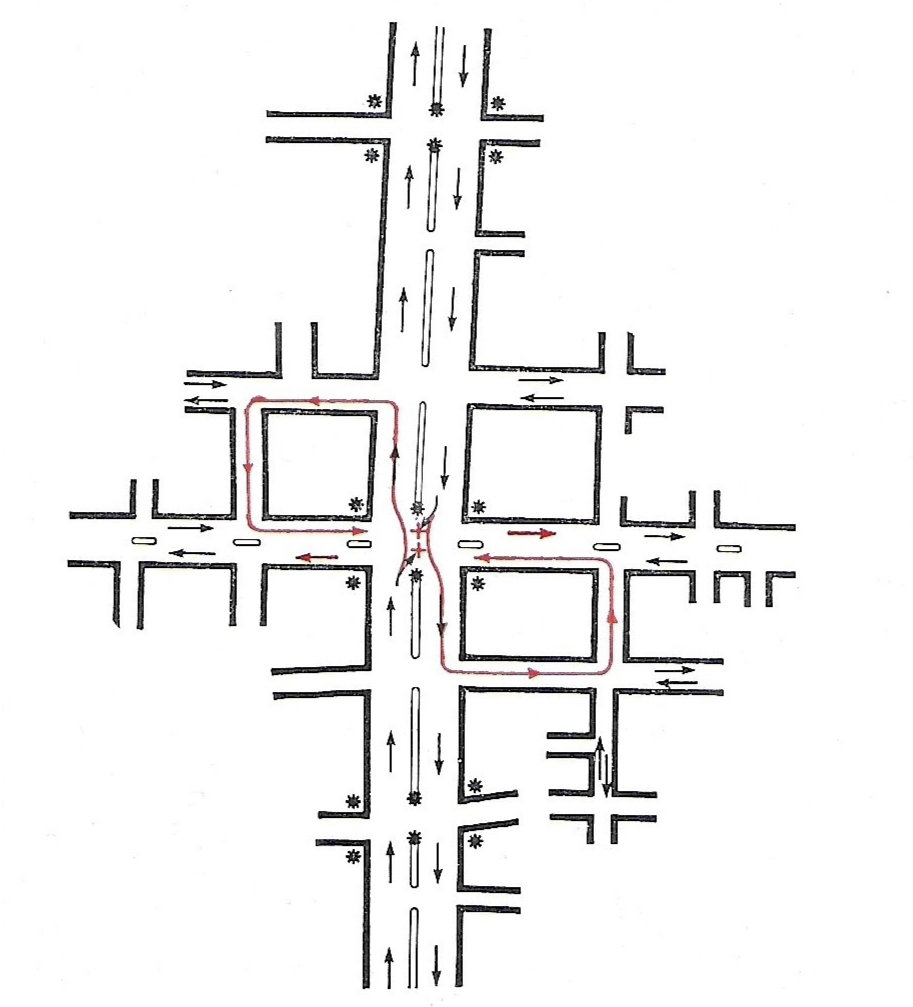

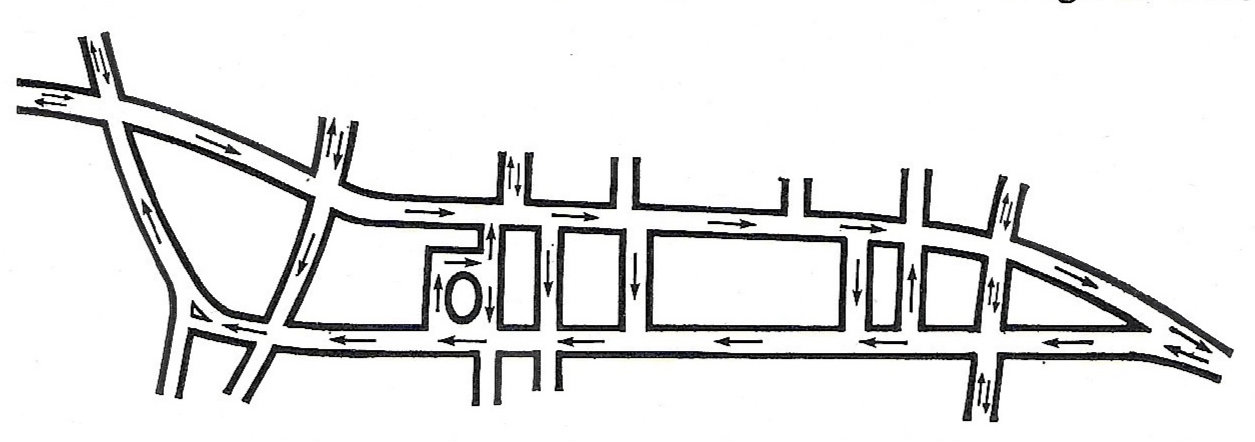

Mention may be made here, in passing, of the new activity known as traffic management. It is not in fact really new, for the management of traffic started when ‘Keep to the Left’ was first thought of, but only in the last few years has it been consciously developed with the objective of

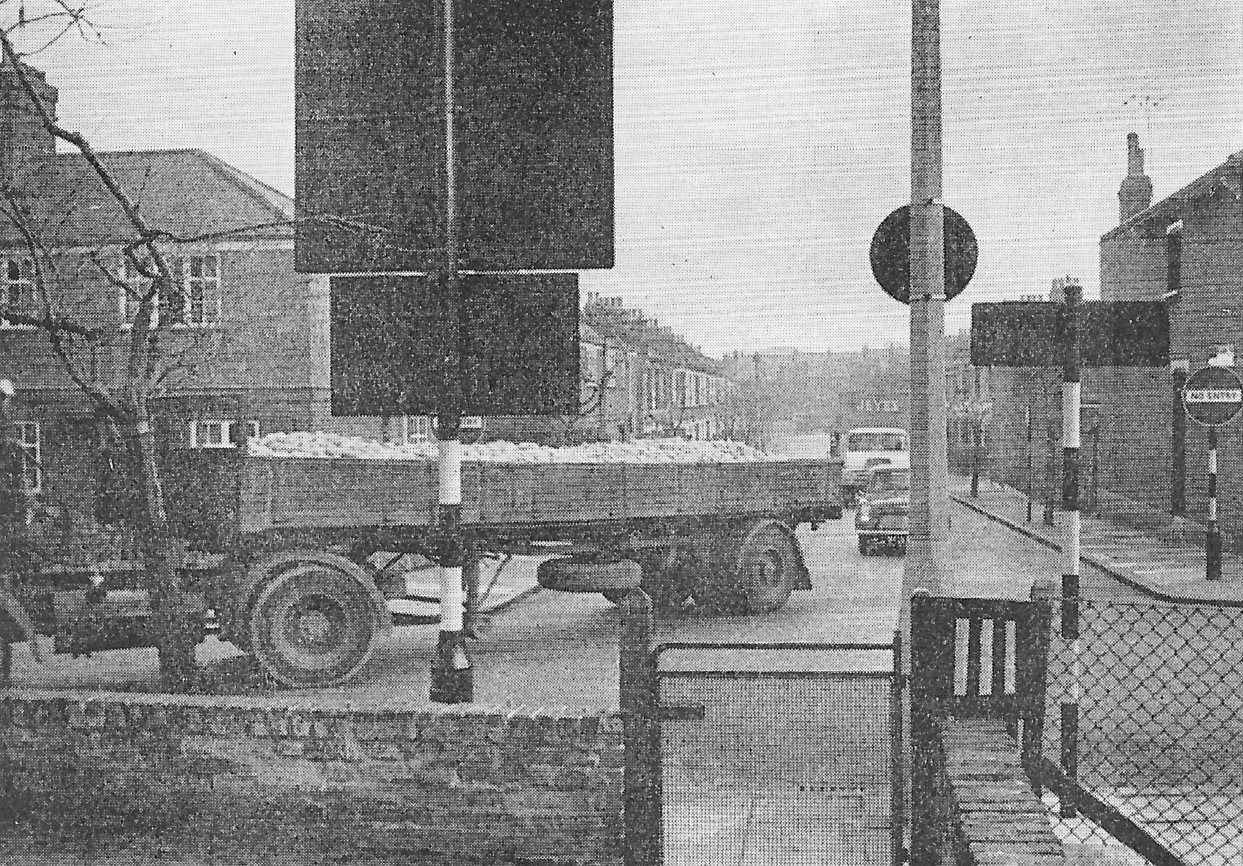

‘getting the most out of the existing street system’. One-way streets and the elimination of right-hand turns have been the main features that have caught public attention, but there are also ‘clearways’, elaborate linked signal installations, the banning or strict control of parking and waiting in many streets, and the closer control of pedestrians. Whilst these measures have been of benefit to the movement of vehicles* it has to be admitted that some of them inhibit the very thing for which motor vehicles are so valuable, namely the ability to penetrate to individual buildings and to stop there. After all, the main purpose of nearly every street in every town is to give access to the buildings along it. Moreover, although in some cases it has been shown that accidents have been reduced, the general effect of these schemes is to increase the speed of traffic and, on the principle of spreading the load, to introduce traffic into streets where it is quite un-suitable, with consequent harmful effects on the surroundings.

* ‘The cumulative effect of various (traffic management) measures in the Central London area have been shown to have increased traffic speeds on main roads by 9% between the autumns of 1960 and 1961.’ Dr G. Charlesworth, Traffic Engineering and Control, Vol. 4 No. 2 June 1962.