Chapter II: The theoretical basis

The basic principle: 100–101

The basic principle is the simple one of circulation, and is illustrated by the familiar case of corridors and rooms. Within a large hospital, for example, there is a complex traffic problem

The basic principle

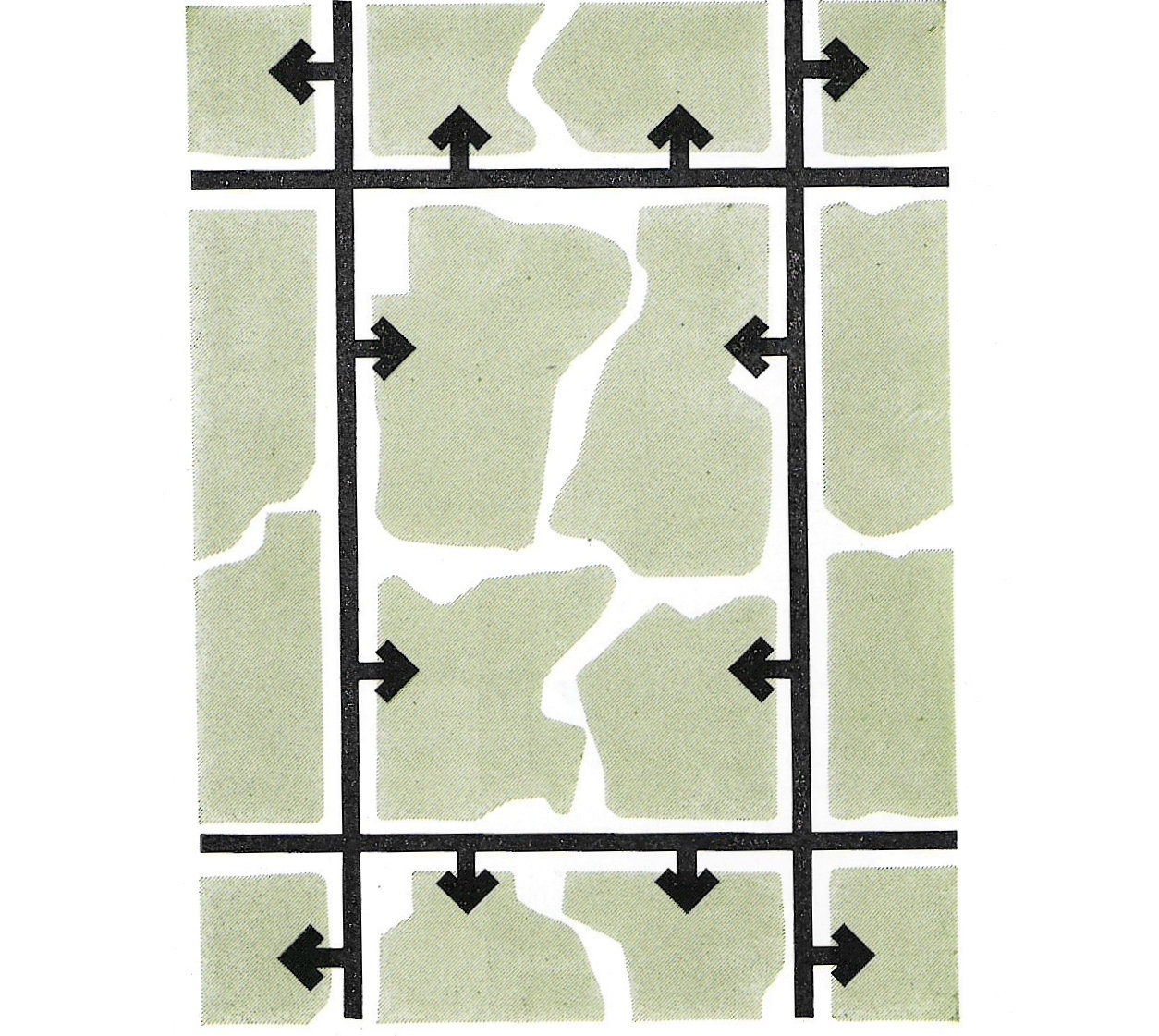

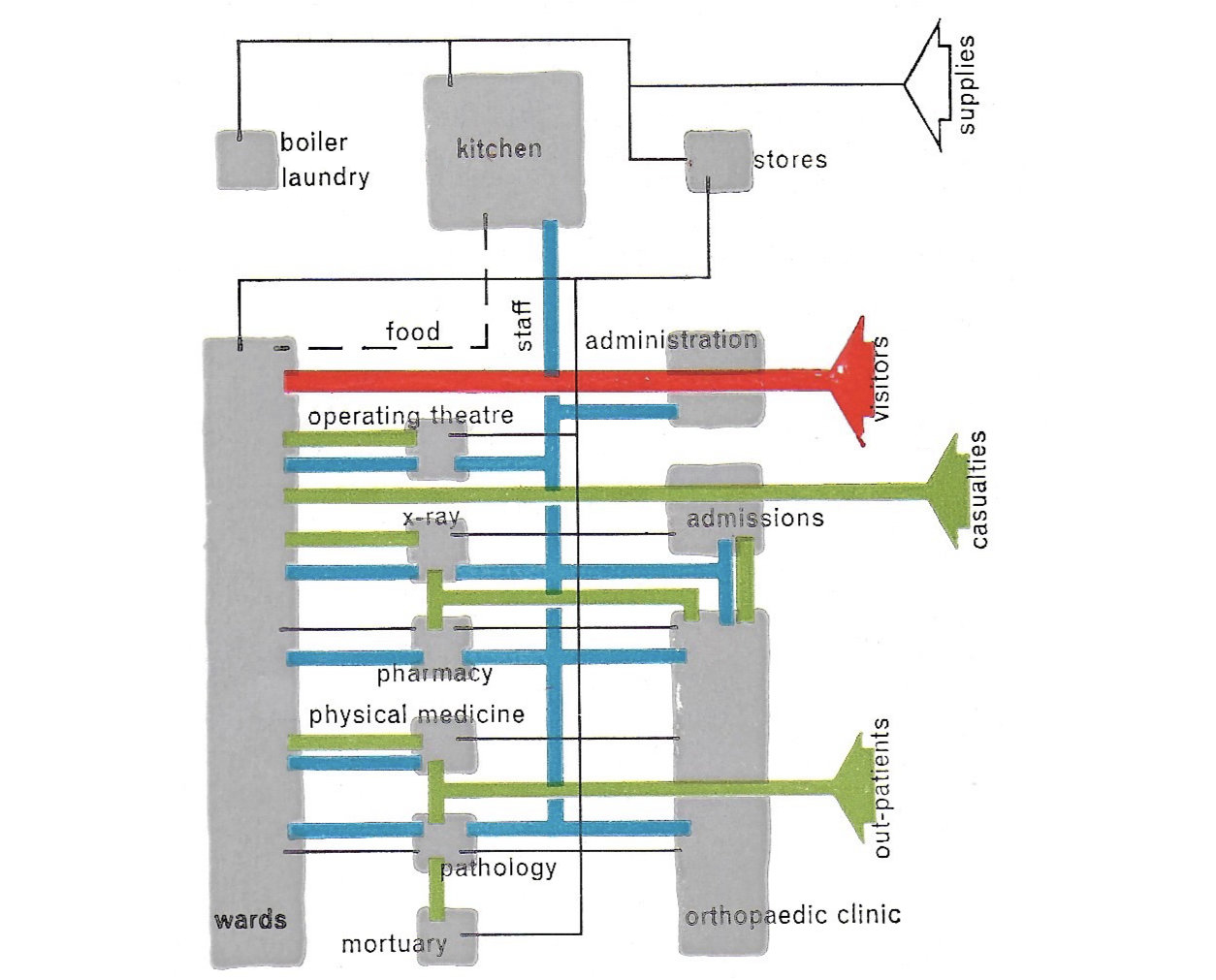

100Fortunately there is no mystery about this, because the problem is no different in its essentials from the circulation problem that arises every day in the design of buildings, where the subject is well understood. The basic principle is the simple one of circulation, and is illustrated by the familiar case of corridors and rooms. Within a large hospital, for example, there is a complex traffic problem. A great deal of movement is involved—patients arrive at reception, are moved to wards, then perhaps to operating theatres and back to wards. Doctors, consultants, sisters and nurses go their rounds. Food, books, letters, medicines and appliances of many kinds have to be distributed. A good deal of this includes wheeled-traffic. The principle on which it is all contrived is the creation of areas of environment (wards, operating theatres, consulting rooms, laboratories, kitchens, libraries, etc.) which are served by a corridor system for the primary distribution of traffic. This is not to say no movement takes place within the areas of environment, since even in a hospital ward there is a drift of movement up and down the ward, but it is strictly controlled so that the environment does not suffer. If for some reason movement tends to build up beyond the ability of the environment to accept it, then something is quickly done to curtail or divert it. The one thing that is never allowed to happen is for an environmental area to be opened to through traffic—food trolleys being trundled through the operating theatre would indicate a fundamental error in circulation planning.

There is no principle other than this on which to contemplate the accommodation of motor traffic in towns and cities, whether it is a design for a new town on an open site, or the adaptation of an existing town. There must be areas of good environment—urban rooms—where people can live, work, shop, look about, and move around on foot in reasonable freedom from the hazards of motor traffic, and there must be a complementary network of roads—urban corridors—for effecting the primary distribution of traffic to the environmental areas. These areas are not free of traffic-they cannot be if they are to function—but the design would ensure that their traffic is related in character and volume to the environmental conditions being sought. If this concept is pursued it can easily be seen that it results in the whole of the town taking on a cellular structure consisting of environmental areas set within an interlacing network of distributory highways. It is a simple concept, but without it the whole subject of urban traffic remains confused, vague, and without comprehensive objectives. Once it is adopted then everything begins to clarify. It is not by any means a new idea, for Sir Alker Tripp was advocating something on these lines over 20 years ago† ,and the precincts and neighbour-hoods of the County of London Plan reflected the same approach. But in the face of the rapidly increasing number of vehicles it acquires a new urgency; it now requires to be explored and developed from a mere concept into a set of working rules for practical application.

† Town Planning and Road Traffic, H. Alker Tripp (Arnold, 1942).