Chapter II: The theoretical basis

Residential areas: 122–125

…the ‘Radburn layout’… was derived originally from English Garden City practice… it has come back across the Atlantic with considerable effect on our own local authority and New Town housing

Residential areas

122Special mention needs to be made of the design of residential areas for traffic. The ‘user requirements’ may be set out as follows:

- Ideally people will want to bring their cars right up to their dwellings, and to garage them inside.

- They will need space reasonably near the dwelling for visitors and tradesmen to park.

- The layout of the area should be easy to comprehend so that residents can have a feeling of locality and visitors can find their way.

- Residents will want to live in conditions of maximum safety and freedom from the nuisance of moving vehicles, and to be able to send their children out to play and to school with the minimum of risk.

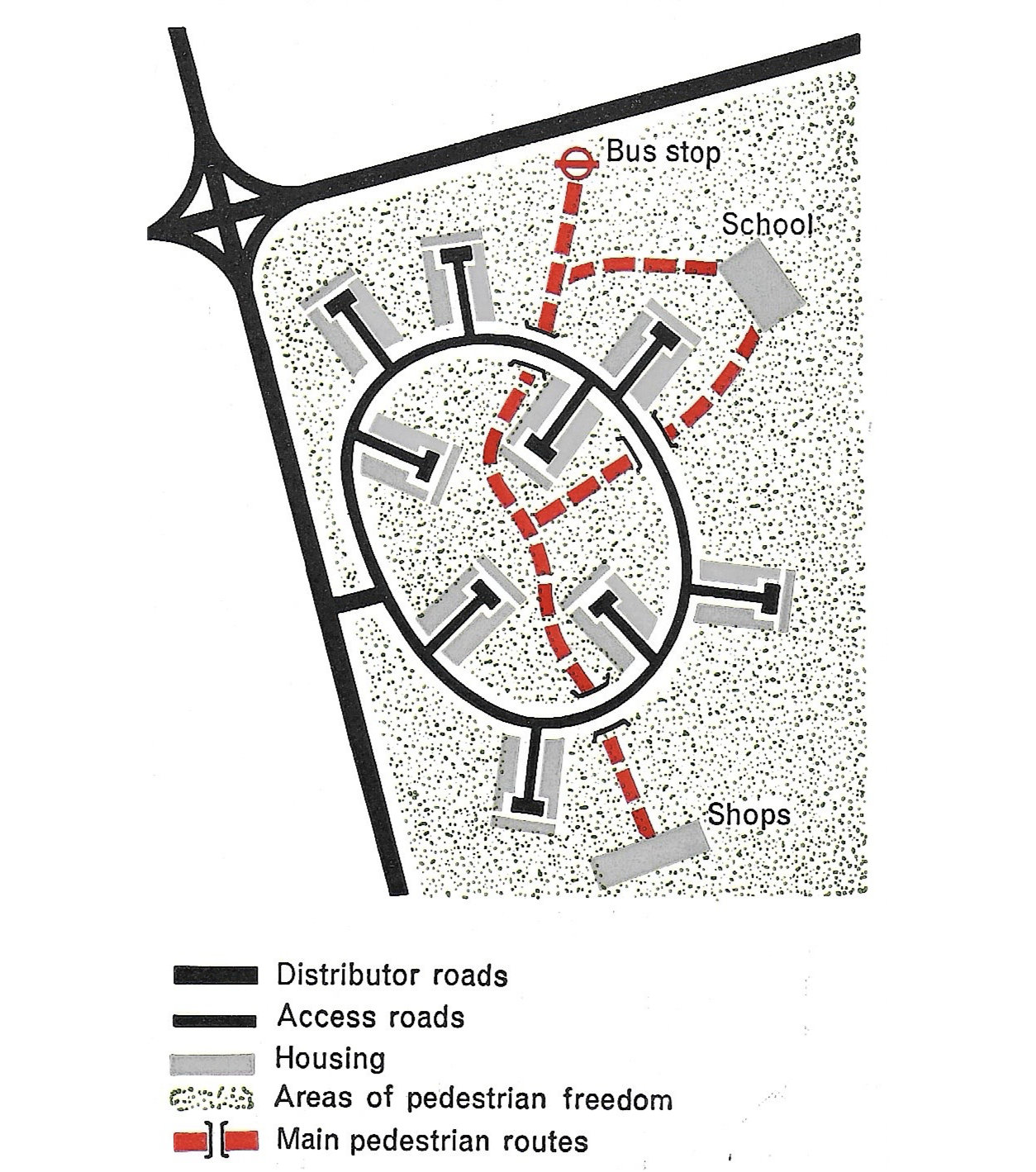

The nearest these requirements have come to being completely satisfied is through what is now commonly known as the ‘Radburn layout’. This idea was derived originally from English Garden City practice. It was exported across the Atlantic to be developed by Clarence Stein and Henry Wright at Radburn in New Jersey in 1928, but seems to have had singularly little influence on American practice. In recent years it has come back across the Atlantic with considerable effect on our own local authority and New Town housing.

124

The main principles of the Radburn system are:

- the creation of a superblock (or, as we would say, an environmental area free from through traffic, and

- the creation of a system of pedestrian footpaths entirely separate from vehicular routes, and linking together places generating pedestrian traffic.

The original Radburn idea is shown in Figure 61 and an example of a layout from Sheffield in Figure 62. The practical effect is that a house has access on one side to a service road or cul-de-sac, and on the other to the independent footpath system. This is in contrast to the conventional arrangement whereby pedestrians and vehicles approach on the same road. The need to apply the principles in full depends largely on the density of the development. Probably the reason why they have had comparatively little influence in the U.S.A. is that so much of the development is so low in density that there is not a great deal of walking around in any case, and what there is seems to be safeguarded by the comparatively mature and considerate behaviour of car drivers. But with the higher residential densities that we are bound to have in this country, and with the greatly increased numbers of cars in the future, the principles are likely to become increasingly useful. The application of the principles does however involve comprehensive designing over sizeable areas. This is possible when the work is being done by local authorities or New Town corporations, but it is very difficult to secure better layouts from private developers with the conditions of piecemeal development in which so much private housing is done.