Chapter II: The theoretical basis

Journey to Work: 84

Every morning, and in the reverse direction every evening, great tidal flows of movement take place between the residential areas and the places of work.

Journey to Work

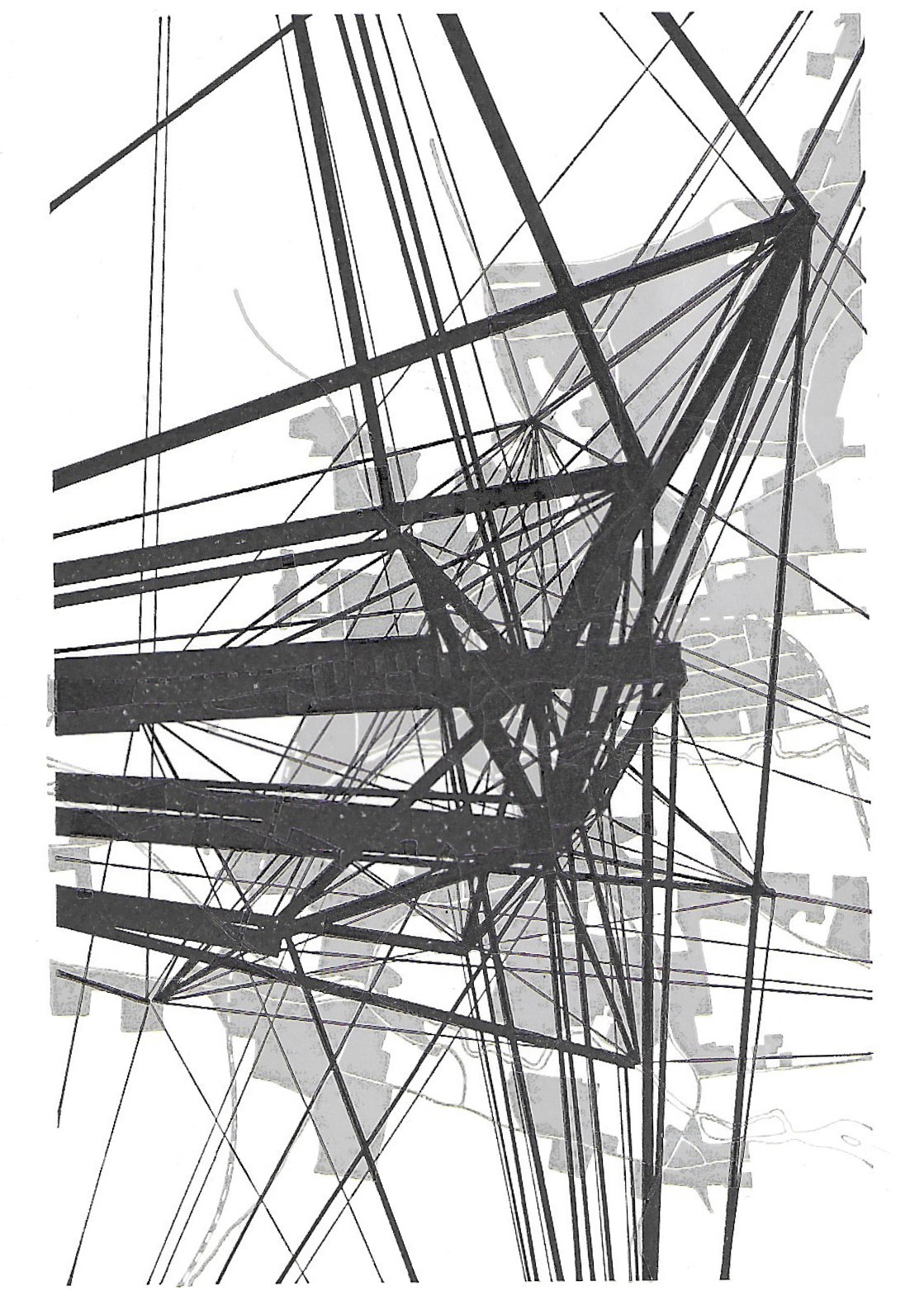

84Certain other features of urban movement may now be distinguished. One of the most basic is the linkage between homes and places of work. In most towns the locations of employment are found to be arranged in a limited number of main groups, together with a considerable scattering in other parts of the town. Every morning, and in the reverse direction every evening, great tidal flows of movement take place between the residential areas and the places of work. The pattern of journeys involved is vividly shown in Figure 48 which is a ‘desire line diagram’ for the work journeys in a town of 30,000 inhabitants. (In such diagrams the commencement and termination of all actual or predicted journeys in a given period of time are represented by points on a map. These points are connected by a straight line to represent the general direction of movement. The thickness of a group of lines thus represents the number of journeys in a particular direction.)

The pattern of travel to work has been becoming more complicated in our big towns over the last half century. As the towns have grown, new dwellings have been constructed round the periphery because no other locations were so readily available. The occupants of these new dwellings, however, have been mainly dependent for employment upon the established work centres. In the replacement of slums also, as a reaction against the crowded conditions of the 19th century, the new houses have sprawled out in suburban estates. This dispersal has brought about better living conditions for millions of people, but the benefits are now tending to be offset by the increasingly difficult travelling conditions which the dispersal has brought about.

86A new phase is now starting in the phenomenon of journey to work. At first, the development of the great suburban sprawls was largely made possible by bus services, though in London and certain other places the suburban railways and undergrounds played a large part. But with the rising standard of living and the consequent increase of car ownership, and because in many places the public transport services seem unable to cope with increased demands, far more people are now seeking to use cars for the journey to work. This is causing the now familiar ‘downward spiral’ whereby public transport loses custom, cuts its services to make up the loss, and then, partly as a consequence of its cuts, tends to lose still more custom.

87In most towns the use of cars for journey to and from work already dominates the traffic picture, and produces the familiar morning and evening ‘peak periods’. As will be shown later, it is this particular form of usage of the motor vehicle that constitutes one of the crucial issues in the urban traffic problem. Closely associated with this is the duration of the peak period—if everyone insists upon travelling at the same time, then more elaborate systems are required than if the journeys are spaced out.