Chapter II: The theoretical basis

Characteristics of networks: 104–112

…any new road cut through a densely developed area will, as a drain cut across a sodden field fills with water, attract enough vehicles to justify its existence in terms of flow.

Characteristics of networks

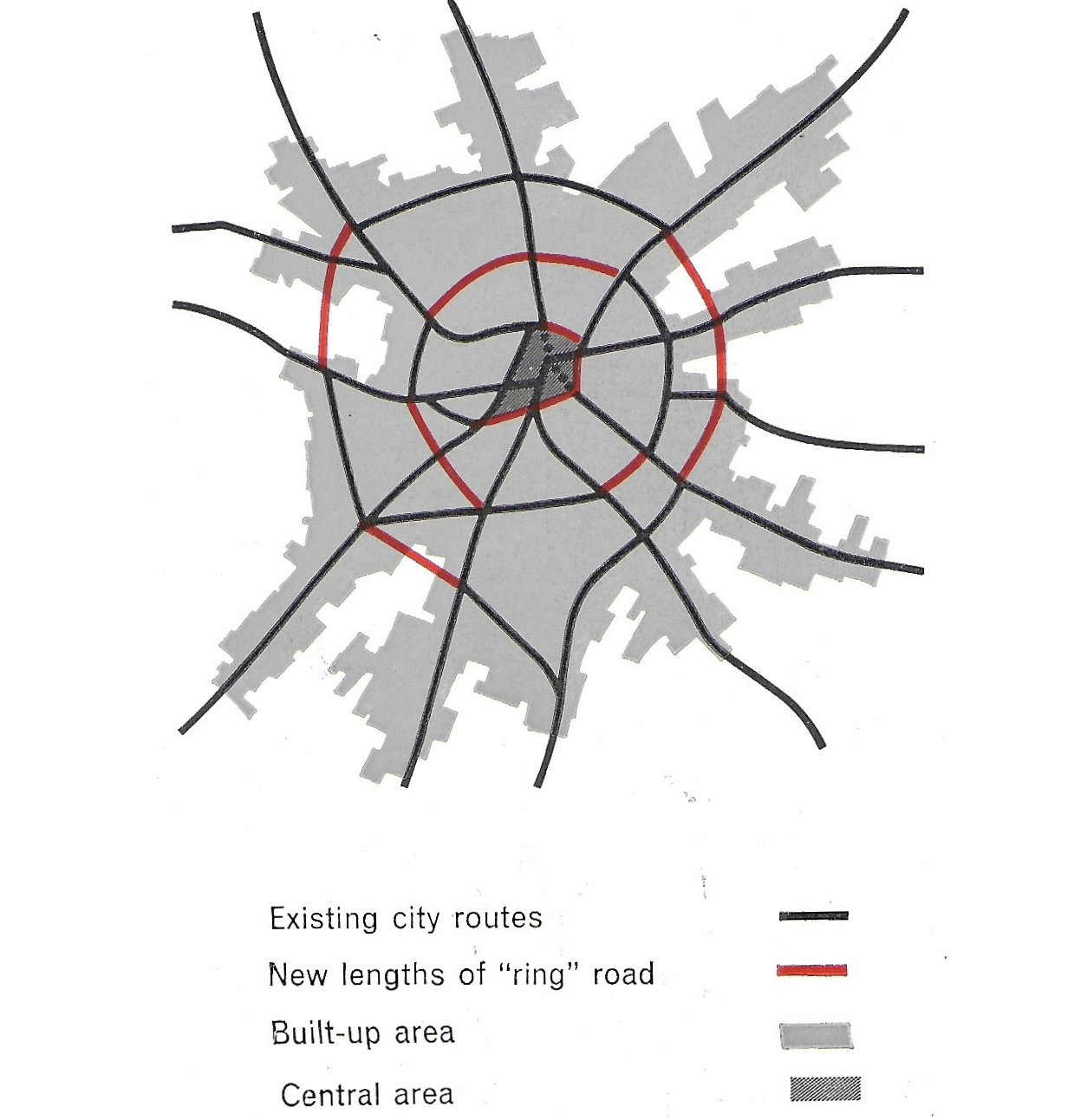

104Pattern. Over the last twenty years or so there has been much discussion and argument about the pattern best suited for the main traffic routes of towns. This discussion has been largely dominated by the idea of ring roads. Historically, most of our towns have developed with a strongly marked radial road system on a more or less symmetrical spider's-web plan (Figure 57). The town centre invariably lies at the centre of the web, but apart from this there may not in fact be any very marked symmetry about the disposition of the other main concentrations of activity. The central position of the business and commercial areas (usually the main traffic generators in the town), the radial road system, and probably the presence of through traffic which has no alternative route, have combined to produce heavy traffic flows on the radials. This has, understandably perhaps, led to the belief that the cause of central congestion is all the traffic pouring in on the radials, and that the obvious ‘solution’ is to divert the traffic round the centre. If the idea of diverting each radial is pursued there very quickly results a complete ring. This is the basis on which the familiar inner ring roads came into being. The intermediate and outer rings of the post-war plans were partly inspired by the same desire to give relief to the centre, but also by the supposition that some kind of outer circumferential routes were useful to connect outer districts. Thus there emerged, by intuition more than by study of actual traffic drifts, the ring road concept and the general idea that this would provide the solution to the main traffic problem. There was an environmental aspect to this proposition as well, because the rings, especially the inner rings, were seen as providing ‘relief’ to the centre where congestion was at its worst. But there has been no attempt to define ‘relief’, nor to set up standards whereby it can be judged whether the relief given is likely to be worth having.

In some cases it appears that ring roads have been intuitively adopted in the first instance as part of the plan, and at a later date ‘origin-and-destination’ surveys have been taken to demonstrate that they would carry enough traffic to justify their construction. The results of such surveys are nearly always favourable to the ring road, for the simple reason that practically any new road cut through a densely developed area will, as a drain cut across a sodden field fills with water, attract enough vehicles to justify its existence in terms of flow. But if a wider view is taken the actual contribution to relieving the centre is extremely uncertain.

106It is not being inferred here that a ring road is in no circumstances likely to form part of an urban network. The objection that is taken is against the slavish adoption of the ring as a standardised pattern. If the problem is considered in terms of a network serving environmental areas (a corridor serving rooms, to use the analogy with buildings) it will be seen at once that the pattern of the network must depend on the disposition of the areas, the kinds and quantities of traffic they generate, the associations that exist between one area and another, or between areas and the outside world. The pattern may eventually comprise a ring, but it must be allowed to ‘work itself out’. In designing the network it is unnecessary, and indeed inadvisable to start with any preconceived intuitive ideas for ring roads, tangential roads, relief roads, internal by-passes, spine roads and the like. All these notions confuse the essential technical issue which is simply the distribution of traffic to areas of buildings.

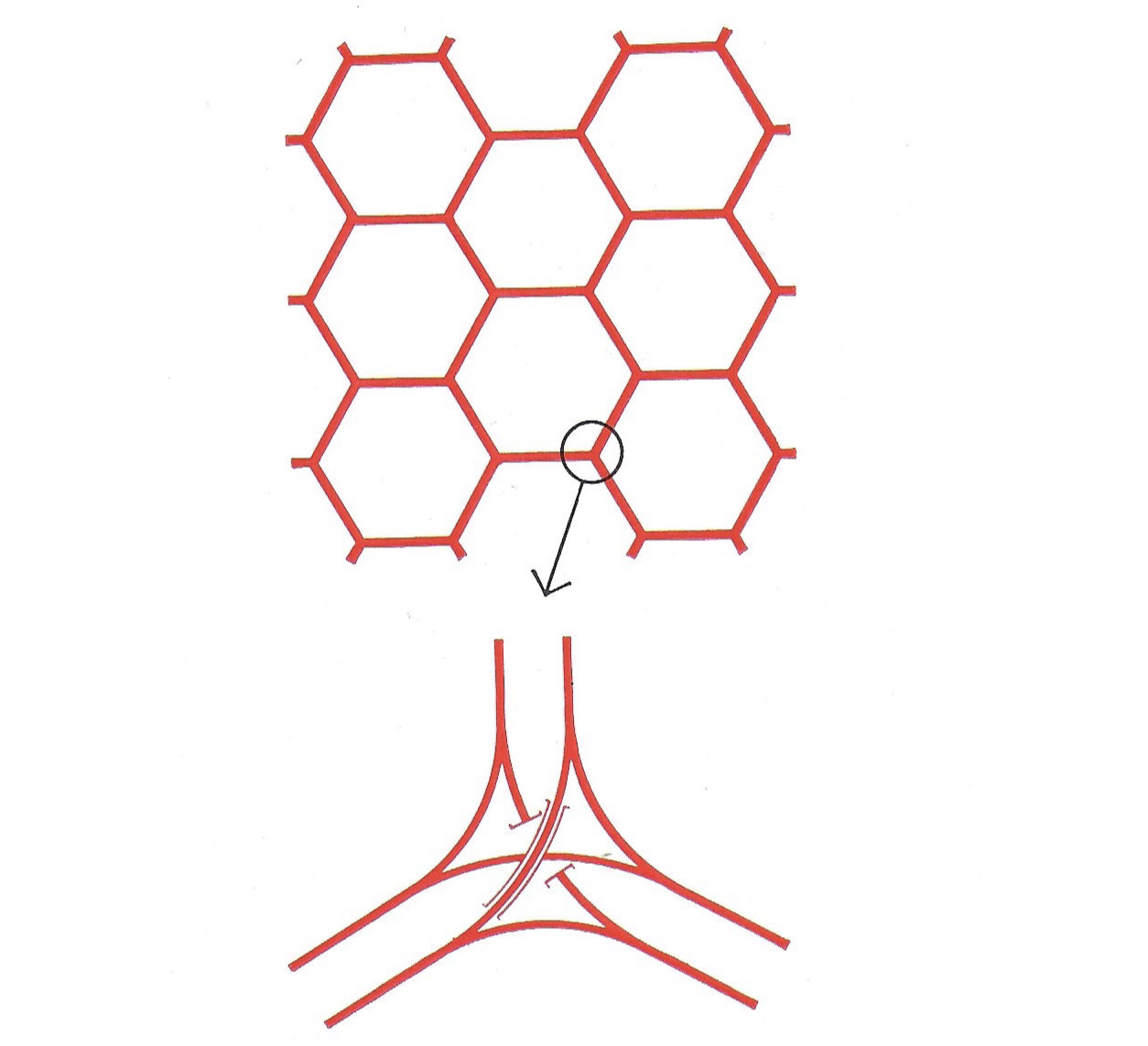

107The only circumstances in which a distributory network would be likely to take on a regular geometrical form would be in the case of an extensive area with a uniform spread of development. In such a case the network would be superimposed in the manner of a ‘grid’ with a definite pattern and ‘module’. A hexagonal pattern (Figure 58) is very efficient, with economical three-way intersections, but other polygonal patterns are possible. A rectangular pattern tends to require very complex intersections. The basic dimension or 'module' of the distributory system in such circumstances will broadly depend upon the kinds and intensities of land uses within the enclosed areas: the more intense the activities, the more traffic will be generated, and so the greater will be the need to insert distributors, and thus the closer will need to be the mesh of the distributory system. Unfortunately the more intense the activities are, the more intense the development is and the more difficult it becomes to insert a proper distributory system.

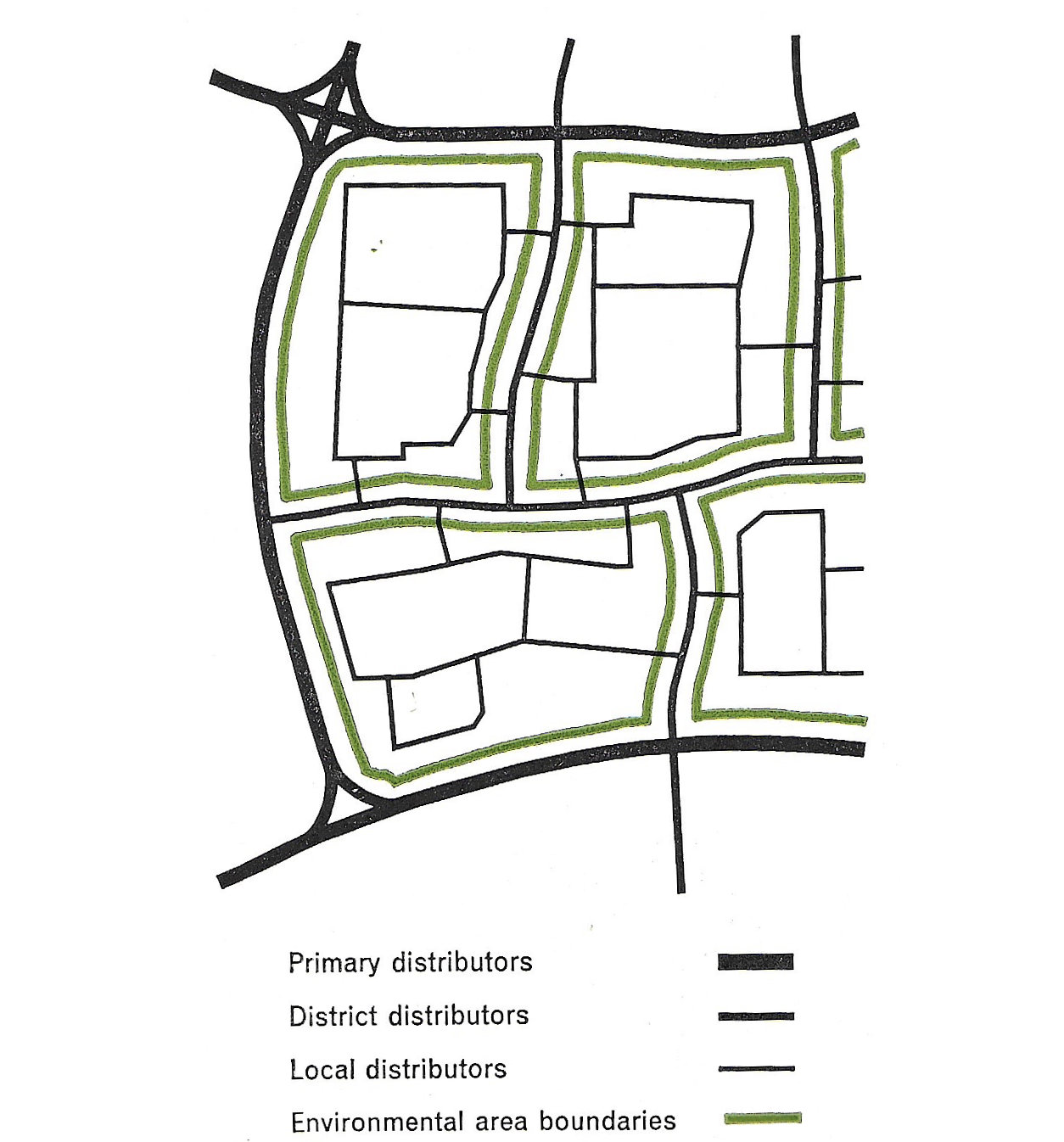

The need for a hierarchy of distributors. The function of the distributory network is to canalise the longer movements from locality to locality. The links of the network should therefore be designed for swift, efficient movement. This means that they cannot also be used for giving direct access to buildings, nor even to minor roads serving the buildings, because the consequent frequency of the junctions would give rise to traffic dangers and disturb the efficiency of the road. It is therefore necessary to introduce the idea of a ‘hierarchy’ of distributors, whereby important distributors feed down through distributors of lesser category to the minor roads which give access to the buildings. The system may be likened to the trunk, limbs, branches, and finally the twigs (corresponding to the access roads) of a tree (Figure 59). Basically, however, there are only two kinds of roads—distributors designed for movement, and access roads to serve the buildings.

The number of stages required in a distributory hierarchy will depend upon the size and arrangement of the town. For the purpose of nomenclature we think it is preferable to refer to the main network of any town as the town or primary network. This may then be broken down into district and local distributor systems as the conditions demand, and in the ‘opposite direction’ it may have to link to regional or even national networks. Thus a primary network for a town of 10,000 population would be likely to be less powerful in character than in the case of a town of 500,000 population, but in both cases the function would be to effect the primary distribution over the town. We think this comparatively simple nomenclature could with advantage replace the present large number of terms—arterial roads, through roads, expressways, freeways, principal traffic roads, collector roads, service roads etc.—which are freely used with little if any standardisation of meaning.

110There is, however, a value in terms which express the standard to which a road is designed. Thus in many cases the links of a primary network as envisaged here would carry sufficient traffic to justify their being reserved for motor traffic only, with fly-over type intersections throughout. This is the specification which has come to be known in this country as a ‘motorway’. We do ourselves, at a later stage in this report, refer to the need for certain distributors to be built to ‘motorway standards’ purely as a result of the volume of traffic they have to carry. A distributor built to this standard and situated within an urban area could be called an ‘urban motorway’. There is no objection to this term as long as it is realised that the function of the road is to distribute traffic, and that urban motorways do not, as many people seem to think, possess some magical property.

111The importance of the details. It is not difficult to devise distributory systems which seem satisfactory at the sketch map stage. The trouble starts when the details are worked out and the great width of the roads and the complexity of the intersections become apparent. This is considered in more detail in examples in the next chapter, but it can be said now that the sheer difficulty of inserting these roads into our cities, except in the simplest form, may well place a limit on the amount of motor traffic that can be accommodated. It is not a matter of engineering difficulties so much as the great amount of land required, the displacement of people and properties which is involved, and the severance and disruption caused by wide roads and big intersections. These effects can be studied in American cities, and the difficulties are manifest. Further reference to this aspect will be found in the section dealing with American practice in Chapter IV.

112The very real possibility has to be faced therefore that practical difficulties of contriving the network could, and almost certainly will, limit the amount of traffic acceptable in urban areas. How these limits stand in relation to the desires of the public, and the consequences if the two are out of balance, is explored in more detail in the next chapter.